[Part 3 of 6] PREPARATORY PRAYER

[Part 1 of 6] INTRODUCTION TO IGNATIAN PRAYER AND FOOD[Part 2 of 6] PREPARATION FOR PRAYER[Part 3 of 6] PREPARATORY PRAYER[Part 4 of 6] GRACE TO BEG FOR[Part 5 of 6] MEDITATION AND CONTEMPLATION[Part 6 of 6] REVIEW OF PRAYER

First to consider at this stage of the Ignatian prayer period is to view it as a participation in a liturgy. As one recites a kind of opening prayer, the exercitant formally enters into the prayer period and start participating in the worship and praise of God like in other forms of liturgy. Before leitourgia took on a religious sense, it used to be any form of public service performed by the wealthier citizens who paid for the singers of a chorus in the theatre or for the food and drinks. Liturgy took on a strictly religious application particularly the ritual service of the temple performed by the priests, for example, Joel 1:9, 2:17, etc. In the New Testament, Zechariah is said to have gone home when “the days of his liturgy” (Lk 1:23) had ended, which indicates that liturgy was gradually established as a formal and religious performance.

Like all liturgies and sacramentals, an hour of Ignatian formal prayer period, is anchored in the sacrament of sacraments or the liturgy of liturgies, namely, the Eucharist, where we are truly nourished by Christ, the Bread of Life. In Sacrosanctum Concilium (SC)—Vatican II’s Constitution on Sacred Liturgy, the Eucharist is touted as the summit and center of all Christian worship. The life of the monastics is the ideal model of structuring not only prayer but all their works or offices around the Divine Office or Liturgy of the Hours.

Just as the Liturgy of the Hours begin with the Invitatory Prayer—“O Lord, open my lips and my mouth shall proclaim your praise”—so too every prayer period starts with a Preparatory Prayer. It is just natural to start a prayer by acknowledging God’s permission to open our lips before we could rightly praise God. It isn’t that we can’t physically open our mouths and say the words, but because this liturgy is both an earthly and heavenly reality. “But the hour is coming, and is now here, when the true worshipers will worship the Father in spirit and truth, for the Father seeks such as these to worship him. God is spirit, and those who worship him must worship in spirit and truth” (Jn 4:23-34). In this light, St Ignatius demands from the exercitant or the one who makes the Spiritual Exercises the interior disposition of con grande animo—with big spirit—the spirit of oblation.

The second consideration, as one formally begins the prayer period, is the agency of the true minister who is Jesus Christ. The Second Vatican Council defines the liturgy as “the work of Christ the Priest and of His Body which is the Church.” Benedict XVI, in his lecture on the Theology of Liturgy delivered during the Journees liturgiques de Fontgombault, in 2001, said that “the essence of the liturgy is summarised in the prayer which St Paul (1 Cor 16:22) and the Didache (10:6) have handed down to us: ‘Maranatha—our Lord is there—Lord, come!’ From now on, the Parousia is accomplished in the Liturgy, but that is so precisely because it teaches us to cry: ‘Come Lord Jesus’, while reaching out towards the Lord who is coming. It always brings us to hear his reply yet again and to experience its truth: ‘Yes, I am coming soon’ (Rev 22:17-20).”

In this sense, every prayer period presupposes that the Lord, who is the minister has already called us first and loved us first. We call to mind this truth in the same way as finding out if one has the invitation to a party or banquet. We cannot just barge in uninvited. Each time we find ourselves in prayer, not only does God invite us first, but God is already waiting for us at our chosen place of encounter. It is said though that God does not need to be told what to do because God already knows everything. But the importance of articulating what we need and naming what one has received already is not to remind God, but for us to be more aware of what we desire or where we are in our pilgrim journey. The door is open, but the knocking is needed for us to do which is more for us than for God. Begging for the grace—demandar lo que quiero—demanding that which I want and desire is first addressed to ourselves than to God. When we are conscious of what we ask in prayer then we too will be alert when God answers our prayer. St Ignatius recommends the following Preparatory Prayer. “I will beg God our Lord [O My God, I pray] for the grace that all my intentions, actions, and operations may be directed purely to the praise and service of His Divine Majesty” (SE 46). Make it a more personal prayer. If possible translate it using one’s own mother tongue—the language of the heart. It is a prayer of humble oblation which is the door to the other virtues. Many saints have attested to the fact that humility is the mother and teacher of all virtues.

The third consideration is the role of the Angels. In the Liturgy of the Catechumens, there comes the great hymn of the angels called Trisagion—“an atrium providing access to the Trinitarian mystery.” The hymn is a typical expression of the praise of the thrice holy God, which arouses the experience in us of the wholly Other and to open in the depths of our hearts a place receptive to the mystery. Let us quote the theologian Eric Peterson: “The whole universe participates in the worship and praise of God. The angels represent the most spiritual part of this universe. For this reason the hymn of the angels can never be forgotten or eliminated from the official worship of the Church. It, in fact, gives to her praise the depth and transcendence which the character of Christian revelation requires.”

Except for the fact that angels are pure spirits, we are all the same by virtue of being creatures. Just like all created beings, angels also require nourishment. This may be strange but it is true: Angels eat! We find one verse in the whole of sacred scripture that refers to angels eating—“Mortals ate of the bread of angels” (Ps 78:25a). It is best that we are aware of this when we start to pray and invoke their help because they become our dining companions or tablemates who do not only eat but they also get hungry and long for satisfaction just like us. One of the earliest Church Fathers, Origen, said of the angels: “They are not only supportive of human beings, but help them in their desire to praise God by praying and imploring Him along with them. So true is this that we even dare to maintain that together with those who have chosen to seek the good and hence who have given themselves to prayer, there are thousands of celestial powers who pray along with them (even when they are not specifically invoked) and thus offer them help.”

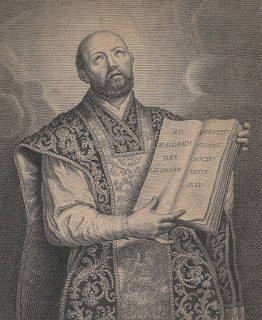

The universal Church has a deeply entrenched belief in the existence of angels as exemplified in her most solemn prayers. There is an old dictum that says: Lex orandi, lex credendi [The rule of prayer is the rule of belief; as one prays, so one believes]. At the heart of this saying is the combination of belief and prayer. In every Ignatian formal prayer period the two are constantly united. When this happens in prayer, i.e., the union not only with the universal Church but with the rest of the universe, as well as the union of the angelic and the human then the prayer becomes a source of true joy. Let us look at the Opening Prayer of the feast of the Archangels, St Michael, St Gabriel and St Rafael: "O God, who dispose in marvelous order ministries both angelic and human, graciously grant that our life on earth may be defended by those who watch over us as they minister perpetually to you in heaven.” A school of biblical exegetes hold that the biblical “angel” is a synonym for God Himself or for the human being. In that sense, wherever and whenever God’s name is invoked either an angel is present or the Divine Godself is guarding and watching over us. Fr JM Manzano SJ

Comments

Post a Comment

Thank you for your interest in the above post. When you make a comment, I would personally read it first before it gets published with my response.